Pop-up Exhibition: Ming Bai—1001 Bottles and Cans

Time: September 3–9, 2025

Reception: Saturday, September 6, 4–7 PM

Suspended between waste and currency, memorial and index, 1001 Bottles and Cans meditates on labor’s tenuous value in a time of inflation and instability. It is both intimate and political: a daughter’s elegy and a structural critique, where each sealed bottle holds not only plastic and glass, but time, care, and endurance. Through the exhibition, Ming Bai transforms an everyday act of survival into an archive of labor, memory, and inheritance.

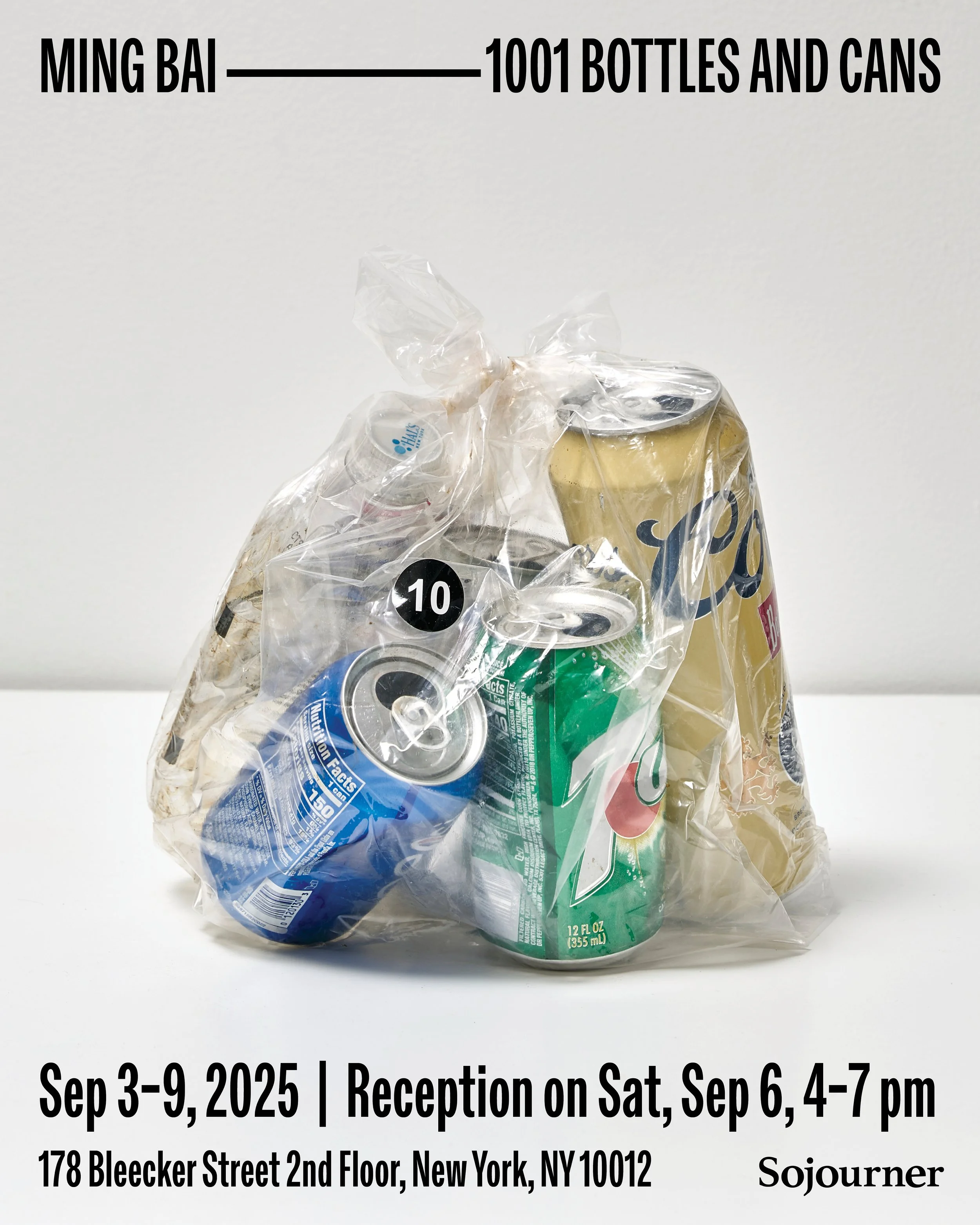

From August to December 2022, Bai collected 1001 discarded bottles and cans from the streets of New York City. Each was photographed in situ, numbered, and sealed in a plastic bag labeled with the day of collection. Together, the bottles record 120 days of walking, bending, and gathering—an accumulation whose redemption value totals only $50.05.

The project echoes the life of Bai’s father, Xinyao (1954–2018), who worked in heavy industry in Harbin before years of odd jobs and bottle collecting. A skilled handyman, he built furniture from scrap wood, fashioned silver jewelry from salvaged fragments of machinery, and carried with him the frugality of a generation shaped by famine, revolution, and layoffs. Bai’s bottles restage his gestures, transforming his quiet persistence into a visible monument.

About the Artist:

Ming Bai is an artist and designer based in New York.

Her artistic practice unfolds in the interstices of her design career and after hours, extending into entrepreneurship, publishing, education, and nonprofit work. It engages with the physical world of people and objects, everyday traces, debates, and the discovery of small wonders and hidden values.

Press Release:

Ming Bai—1001 Bottles and Cans

By Rain Chan

In Ming Bai’s solo exhibition 1001 Bottles and cans, every object is both painfully ordinary and profoundly allegorical: a street-castoff container, timestamped and sealed, reverberates as currency, archive, and elegy. Over the span of 120 days in the summer and fall of 2022, Bai picked up precisely 1001 bottles and cans around the Lower East Side streets in New York City, where refuse and renewal endlessly collide.

The entire corpus is meticulously numbered, bagged, and preserved. The act of collection generates a ledger: daily tallies, productive days of thirty bottles, absences marked as zero, the statistical mundanity of labor. The final redemption value of the project amounts to $50.05—the meager equivalence of thousands of steps, countless glances downward, countless gestures of bending, reaching, sealing.

But Bai’s bottles do not seek to be redeemed. They refuse liquidation, insisting instead on remaining as an archive of embodied time. Each bagged fragment testifies to the intensification of precarious labor under conditions of inflation, pandemic fallout, and rising costs of survival. Each is also a metonym of a paternal inheritance: Bai’s father, Xinyao (1954–2018), once a machinist in Harbin’s heavy industries, later a handyman and an informal recycler, persistently gathered bottles for spare cash throughout his life.

1001 Bottles and cans introduces dual scale and temporality: the macro-historical framework behind capital’s devaluation of labor, and the fleeting, particular time of a father who once pressed crisp 100-yuan bills into his daughter’s hand with the simple injunction, “Eat something good.” Like the silver bracelet and ring forged by Xinyao’s act of collecting, Bai’s sealed bottles alchemize the trivial into the memorial.

In its insistence on material form, 1001 Bottles and Cans recalls traditions of conceptual and durational art, yet it refuses the autonomy of the art object. Instead, it situates itself in the circulation of use and exchange: the bottle as waste, as cash-equivalent, as mnemonic relic. By repeating and preserving her father’s gestures, Bai re-stages familial memory as economic allegory, personal inheritance as social critique.

This exhibition emerges not as a nostalgia piece, but as a critical meditation on labor, value, and accumulation. It asks: What is the worth of work, when work is survival? How does love persist through economies that render both objects and people disposable? And what might it mean, in a moment of inflationary precarity, to collect not capital, but time itself?